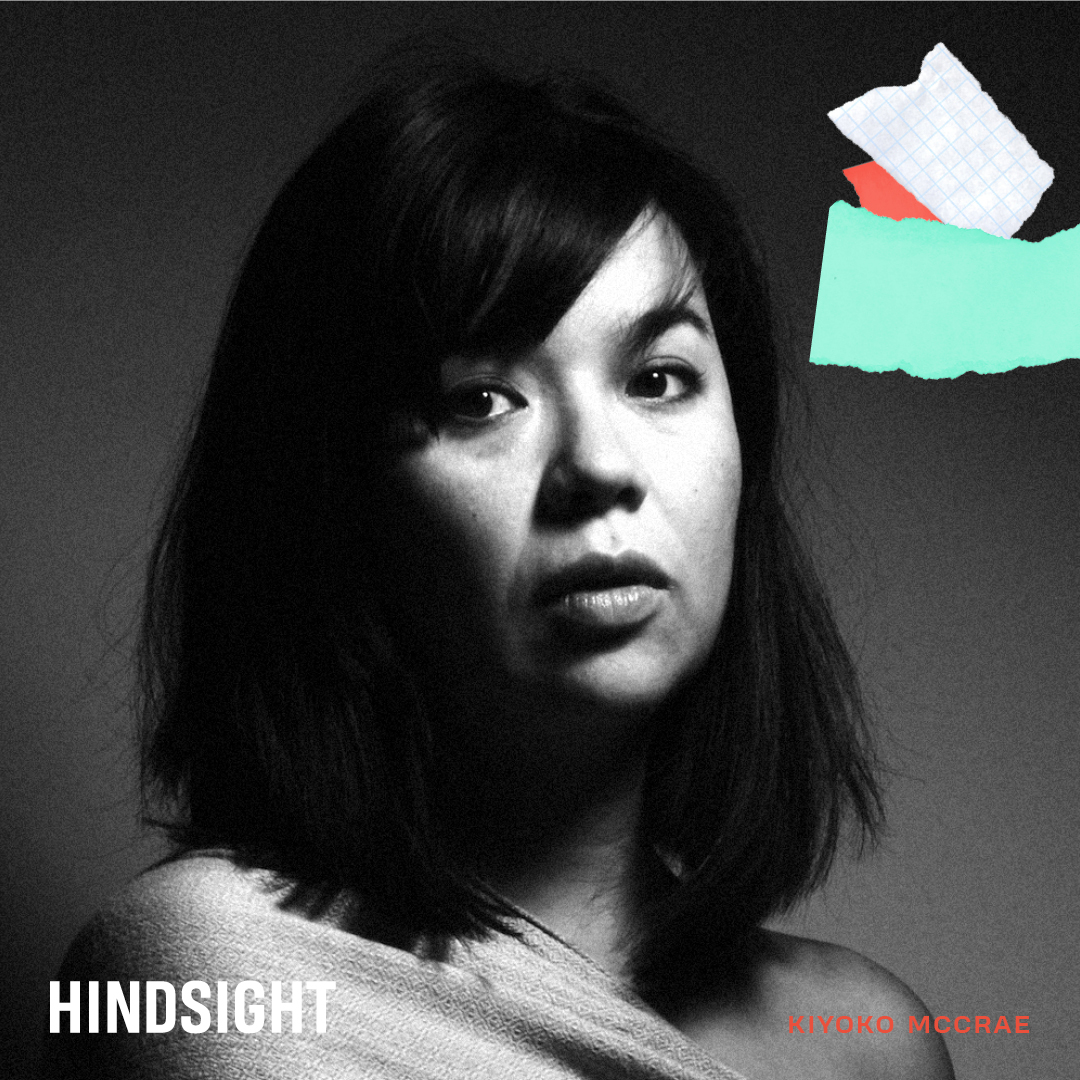

The third film featured from our Hindsight project with the Center for Asian American Media, Firelight Media, and the World Channel is "We Stay In the House," which provides an intimate portrait of four mothers in New Orleans as they struggle to care for their families and themselves throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Between taking care of their children, finding time to work, and coping with personal loss and health crises, these women's stories represent the lived realities of millions of mothers in America. Reel South producer Nicholas Price connected with the director of the film, Kiyoko McCrae, and she sheds an intimate look into the filming of their stories in the filmmaker interview below.

Nicholas: New Orleans was one of the first major tragedies of the pandemic. What was it like seeing your community represented at that moment?

Kiyoko: It’s surreal to see that moment now, especially as cases are skyrocketing again now. We are basically right where we were at the beginning of the pandemic. Right now, it’s hard to imagine ever being able to celebrate Mardi Gras or any other gathering on the streets, again. Looking back at it now, Mardi Gras was the last big celebration before all of our lives were turned upside down. It is bittersweet to look back at those images. It seems impossible that we didn’t know what was about to happen and how our lives were about to change. I hope my children are able to remember the feeling of celebrating without worry and fear. They have become so conditioned and accustomed to fear being in large groups now that I’m not sure they remember the joy of celebrating in the streets anymore.

Nicholas: Do you think the mothers’ perspective what missing during 2020? How does this film respond to or create that narrative?

Kiyoko: Yes, absolutely and not just mothers. So many perspectives were overshadowed by the many crises of 2020. One of the hardest things was having no control over the public health guidelines and policies knowing full well that we were going to be directly impacted by school closures. It became clear to many of us in the summer of 2020 that the lack of federal, state, and local coordination of public health guidelines and mandates was going to lead to school closures.

I had the impulse to organize amongst mothers and parents to demand that the government have a plan in place to support parents in the event that schools would be virtual. If they weren’t going to be in school, someone was going to have to pay the price for taking care of them. It was clear that parents, namely mothers, were going to have to pay that price. Since we couldn’t pay it with money we didn’t have, it was going to be paid with sweat equity. In many cases, this meant losing work or losing sleep or both. It didn’t seem like there were any conversations happening on the national level about the federal government’s responsibility to provide any kind of support for childcare. I wanted to organize to demand financial support for parents to pay for tutors – things that wealthier people could afford. I would stay up late at night worrying about what would happen if our kids couldn’t go to school. How would I get my work done? How would I teach them? What should we be doing to organize? Would anyone listen? But of course, like others, I didn’t have the time or energy to organize. I felt helpless and frustrated. As mothers, we had the foresight to know what the school year would look like and how it would impact us, but there was no one who would hear our concerns.

I started talking to more friends who were mothers and looking into Facebook groups of mothers in New Orleans and nationwide. I found an overwhelming number of mothers, versus fathers, were taking the brunt of childcare responsibilities for whatever reason. Mothers were either laid off from jobs, chose to leave jobs, or cut down on their hours in order to care for their children. What started off as a temporary solution has become more and more permanent and I fear that millions of women are having to put aside their careers longer-term. This is no longer a temporary situation and will have repercussions that will last for years.

For those of us who were able to hang on to jobs or contract work, there’s been this underlying sense of always apologizing for having to take care of kids. I felt invisible, like so many women. Many women experienced a lack of understanding from employers, clients, and others who were not necessarily accommodating to this new reality.

It seems that there is never time for oneself anymore. Even as I write this, I have one child who is crying out of frustration and the other who needs help putting on their clothes. I write in five-minute spurts and broken concentration. It is the new normal. Late nights are the new normal.

Nicholas: The creative community in New Orleans here survived but what challenges are you all facing now and what do you need to keep going?

Kiyoko: New Orleans' creative community, like so many places, is really struggling. In Louisiana, Governor Edwards ended unemployment benefits on July 31st, months ahead of the federal unemployment aid expiration date of Sept. 6th. Those who are dependent on the gig and tourism economy have been hit the hardest. There was a real sense that we would be moving into the fall with some kind of return to normalcy but that has now been shattered. Jazz Fest and French Quarter Fest which were scheduled to happen in the fall after being rescheduled twice have now been canceled again.

As of August 2nd, Louisiana ranks number one in the world for COVID-19 cases per capita. If Louisiana were considered to be a country, it would be ranked number one in the world. The numbers are staggering and it’s hard and surreal to think that we are right back where we were at the height of the pandemic. In fact, we have more cases now than we ever have.

One of my closest friends — her partner and their four kids just left New Orleans this week because the city can no longer support them as musicians and performing artists.

People are adapting best they can but it’s almost impossible to keep up with the ever-changing landscape. Many musicians have found other income streams through live streaming. Those who have management teams have been able to find some work through local live performances and touring which just started back up this summer but the future is uncertain. Others, like Tiffany and Lauren who are featured in the film, have been providing more diversity, equity, and inclusion training in the arts and teaching theater management. Lauren’s theater company has been producing and presenting theater online and Ashleigh has adapted to doing stand-up comedy online.

In this last year, we have lost three black women actors and writers who were pillars of the film and theater community in New Orleans, one of whom Lauren talks about in the film. She is talking about Carol Sutton, an actor and mentor to her and many in the community who passed away from complications of COVID-19. Sherri Marina, another closer friend of Lauren’s, is another beloved actor who passed away in 2020. She was diagnosed with cancer after having contracted COVID. Most recently another legend, Adella Gautier passed away.

The New Orleans arts community continues to struggle and it’s unclear if things will ever return to the way they were.

Nicholas: What does it mean to you to be making this (your) film in this moment, and in this South?

Kiyoko: New Orleans was one of the hardest-hit cities in the country, disproportionately affecting black communities. While our city has taken stringent safety measures, surrounding red counties have varying attitudes and lower vaccination rates. We are in a constant state of limbo and children and mothers are caught in the middle of ever-changing school policies. This is emblematic of the dichotomy of many communities across the South where political divisions and contradicting policies have led to dire consequences for public health. The divisions in the South have never been felt more starkly than in this moment. As mothers, we are bracing ourselves and figuring out how to best protect our children as we learn that more and more children are hospitalized with severe COVID-related illnesses. As of early August, Louisiana’s children’s hospitals are stretched thin with record hospitalizations.

In many ways, we are heading into a fall that will be a real test of survival. I could have never imagined that 2020 might be a warm-up for 2021 but it is starting to feel that way.

Nicholas: What was it like for you working with public television for the first time?

Kiyoko: It has meant so much to have public television support behind this film. I have always wanted to reach as wide an audience as possible because I know that this has been a lived reality for so many women.

Nicholas: What do you want the audience to know about this community you have documented?

Kiyoko: In the United States we create all kinds of myths that make it easier to turn a blind eye to our problems. There is the myth of meritocracy — this idea that we just need to pull ourselves by the bootstraps to be successful. We love stories about the student who rose from poverty to get into an Ivy League school against all odds. We marvel at the single mother who works three jobs and gets a college degree. Through this pandemic, I’ve seen the myth of the “supermom” reinforced time and time again. We are expected to do everything and be everything. We are applauded for being strong and resilient and positive through it all. Yes, women are incredible, and we should be applauded for our accomplishments, but we should not be expected to be the catch-all provider for all of our children’s needs at the expense of our own well-being. If we continue to believe these myths that support the idea that we can get through anything or that anything can be overcome, it keeps us from taking responsibility for the failures of our government and institutions to provide basic human rights, regardless of whether or not we are living through a pandemic. It allows capitalism to flourish without consequence. These issues have existed prior to COVID-19. They have only been exasperated and brought into greater focus by COVID.

Nicholas: What’s next for you?

Kiyoko: Pre-COVID I had planned to work on my first feature documentary "Within, Within," which has been in development with support from CAAM and Southern Documentary Fund. In this film I retrace my grandmother’s footsteps by returning to her hometown Tokyo, weaving a tapestry that is part memory, part speculation, blurring the lines between documentary and narrative. Blending stories of family members, poetry, and animation, it is anchored by my imagining of my grandmother’s life in post-war Japan, when she was pregnant with my mother, who in turn was carrying the seed of myself, within, within. Through this journey, I aim to uncover the legacy of war and the healing power of memory. With the support from CAAM and SDF, I was able to travel to Japan in 2019 with my family to interview family and shoot some preliminary footage. I hope to be able to pick up where I left off and start planning for production.

Category

Share